Historian and CovSoc Committee member, David Fry, has been studying past editions of the Alfred Herbert Newsletter. These Newsletters are much more than just a works magazine and some articles give an invaluable insight into the thinking in the city at the time they were written. The article below is extracted from a 1957 edition, looking back at past years of activity in the busy post-war city, and is written in the idiosyncratic style of an Alfred Herbert’s employee.(captions are as originally written)

From Alfred Herbert News Vol 31 No 2 March-April 1957

The excitement of the Coronation was over and Coventry, still very elated over its Lord Mayoralty, once more turned to the apparently unending, but now quite interesting, business of rebuilding the city.

On June 18th Ford’s Hospital, one of Coventry’s architectural gems which had been severely damaged by air raids, was formally re-opened by Sir Alfred Herbert.

July brought the welcome news that an armistice had, at long last, been signed in Korea. It also brought the much less welcome news that Coventry was facing another coal crisis.

Bad news also followed good in August.

On the 14th Woolworth’s magnificent stores in the Precinct was opened and on the following day—a Saturday—the city was without buses, for the transport workers said there would be no more buses on Saturdays until their objections to new schedules had been overcome.

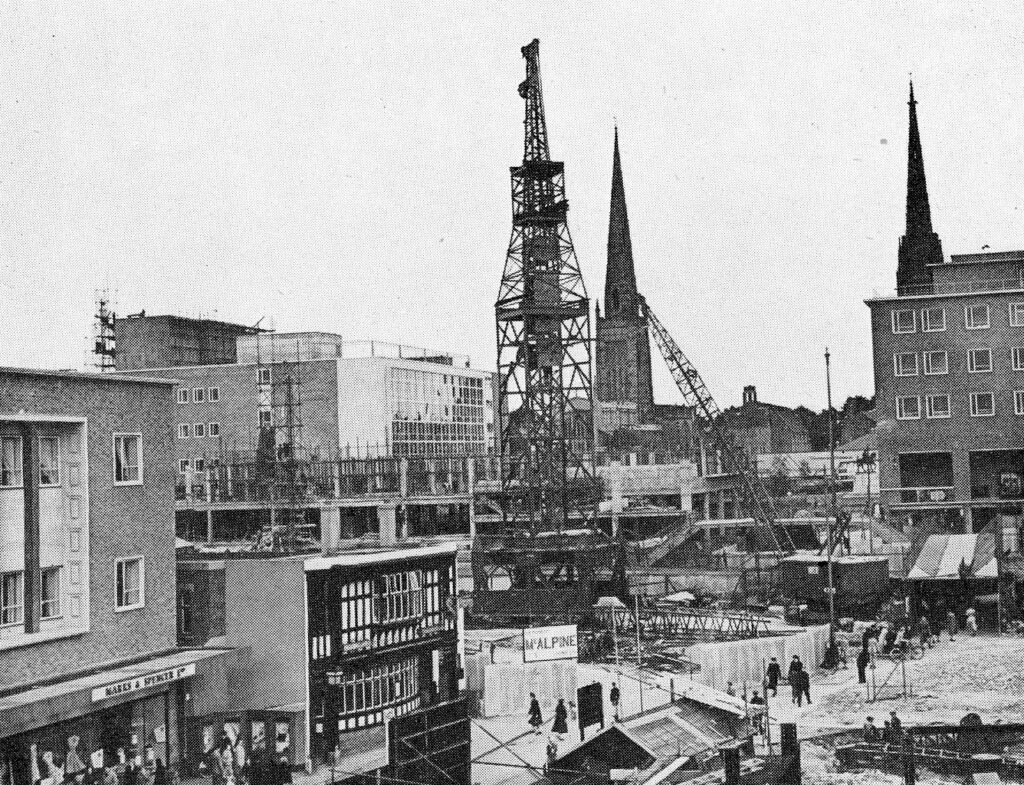

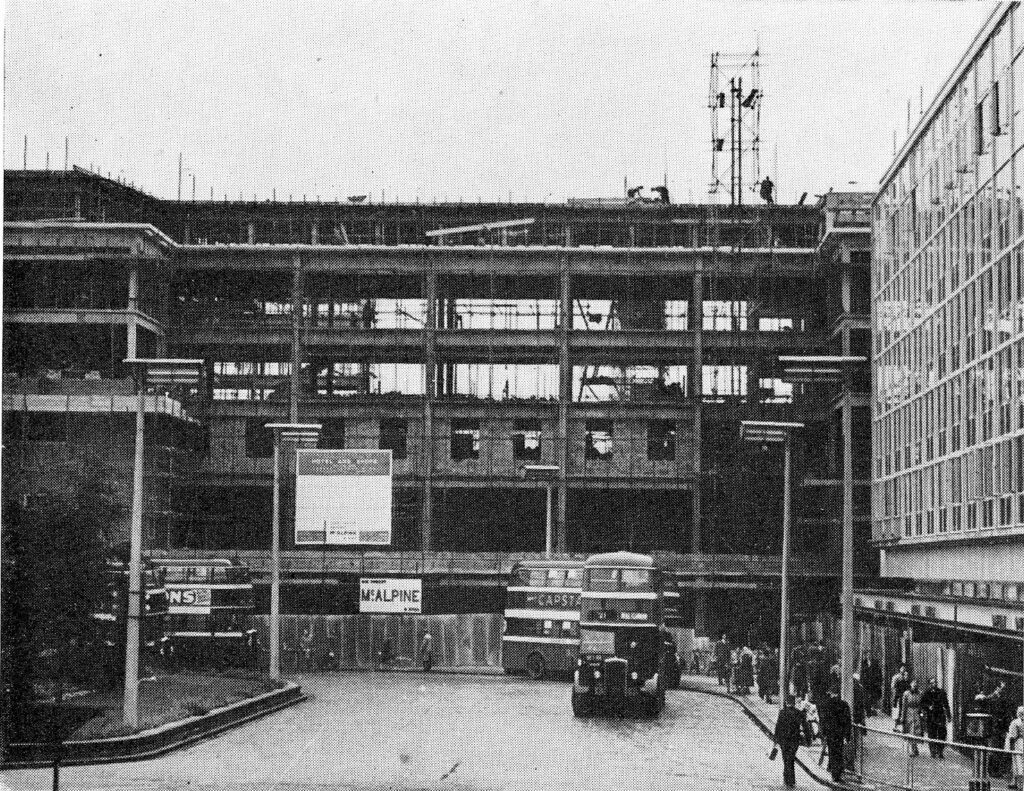

By the end of August the new Marks and Spencer store could be seen to be rapidly taking shape and the demolition of the New Arcade had commenced. How proud Coventry had been of its gleaming white, airy arcade which had replaced the grubby old passage leading to the Barracks Market. And now the new was being demolished to make way for the newer.

On September 7th the Provost of St. Michael’s, the Very Reverend R. T. Howard, Reverend C. E. Ross, left for Canada on a tour which they hoped would result in donations totalling £100,000 towards the cost of building the new cathedral.

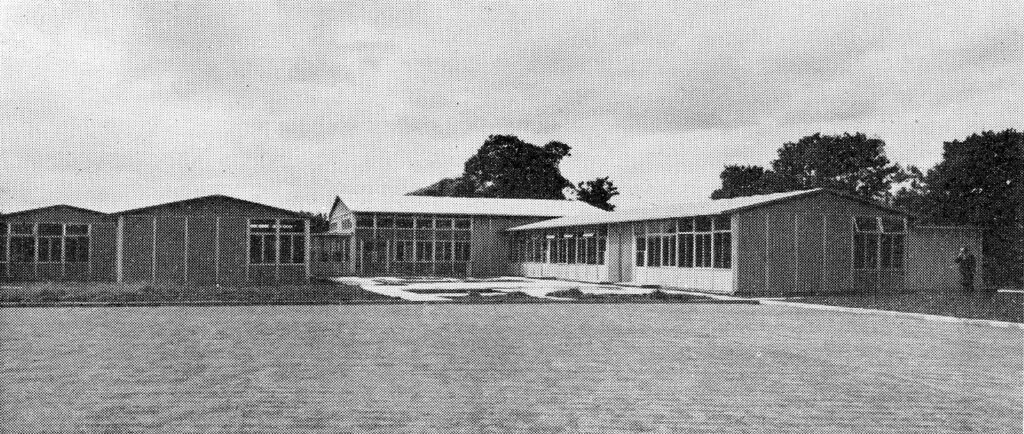

In the meantime, innumerable schools, towering flats, and housing estates were seemingly springing up everywhere.

And still the dislocation of pleasure and business continued every Saturday through lack of public transport until the Corporation was forced to break the strike on September 26th by threat of wholesale dismissals.

October 2nd brought very good news to Coventry, for on that date Sir John Black announced that the Standard Motor Company intended to build immediately a new factory at Banner Lane, at a cost of £1,000,000, solely for the production of the new “Standard 8” car of which it was hoped to produce 400 daily.

Again another little bit of old Coventry had to make way for the new, for on October 3rd the stalls in West Orchard Market—all that remained of the once huge Coventry Market—were removed to a new site adjoining Corporation Street in order that clearance work could commence for the new hotel block.

On October 24th the Duke of Edinburgh paid a flying visit to Coventry.

Arriving at 11 a.m. he was officially welcomed by the Lord Mayor at the Council House after which he drove to Whitley where he formally opened the Butlin Holiday Campers’ Playing Field.

It was indeed a very short visit, lasting just over an hour, but that Coventry was pleased to see him was evidenced by the dense crowds that lined the route and packed the playing field.

On November 3rd Coventry was saddened to hear of the death of one of its most prominent industrialists, Lord Kenilworth. John Siddeley, as he was then, joined the Deasy Motor Car Manufacturing Company in 1909 which then became the Siddeley Deasy Company. Ten years later the firm amalgamated with the car division of the Armstrong Whitworth Company to form Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Limited.

Mr. Siddeley was created the first Baron Kenilworth in 1937 and later gave the famous castle, from which he took his title, to the nation.

He also gave £100,000 to the new cathedral and in 1951 presented the Corporation with a magnificent collection of silverware and tableware.

His death at the age of 87 years removed yet another of those brilliant men who had helped to build the city’s industrial greatness.

On December 1st a pleasing little ceremony took place in St. Mary’s Hall for on that date the Coventry and District Engineers Employers’ Association presented the city with some exquisite silverware and a clock—all made by Coventry craftsmen— to commemorate the granting of the Lord Mayoralty to the city.

And then, once again, the grim spectre of industrial unrest reared its unwelcome head. For some time the engineering unions had been pressing for a substantial wage increase which the employers had refused. As a result the unions called a 24-hour strike with the threat of further national dislocation should their demands be refused.

A fortnight later the Provost and the Bishop’s Chaplain returned from their tour of Canada with the very heartening news that £20,000 had been subscribed by Canadians towards the cost of the new cathedral.

As Christmas approached it was obvious that it was going to be one of the best for many years. All the shops were filled to overflowing with goods of every description which the people of Coventry, with plenty of money to spend, were not reluctant in buying.

Even the weather—unseasonable though it was—contributed to the general gaiety with really spring-like sunshine.

The epitaph of the old year was pronounced by a local newspaper which said “The end of 1953 finds the people of this country experiencing prosperity at a level never enjoyed before”.

But, if 1953 ended with optimism, 1954 soon produced discord.

On January 4th a heavy snowfall blanketed the country and, as though to coincide with the onslaught of winter, it was announced that the price of coal was being increased by 2/3d a ton.

On the following day speculation reigned in Coventry when it was learned that Sir John Black had resigned his position as Chairman and Managing Director of the Standard Motor Company.

And then, on the 18th, the city was shocked and horrified to learn of the brutal murder of Mrs. Mogano of Radford who was found battered to death at her home.

Investigations proceeded at full speed but as the weeks lengthened into months and the months into years it appeared that justice was being defeated.

Again the new cathedral came into the limelight when, on February 3rd, the members of the Coventry Council stated “quite emphatically that it is not opportune to build the Cathedral at this time”.

Why this should be so was very difficult to understand, for even the worn-out objection that it would detract from the building of houses was rendered somewhat fatuous in view of the self-same Council’s eagerness to start the building of the Civic Theatre, a project which would most certainly require house-building labour— and even house bricks.

The building trade’s journals as well as architects all over the country supported an immediate start on the cathedral in no uncertain manner.

It was therefore not surprising—even though it was an almost unparalleled rebuke to a City Council of such standing as Coventry’s—that when the Cathedral Reconstruction Committee applied to the Ministry of Works for a building license it was granted almost immediately.

Then on April 6th the members of the Council proceeded to place themselves once again in an invidious and hotly criticised position. They decided that in view of the enormously devastating power of the new H-bomb the Civil Defence Corps of the city should be disbanded.

This attitude aroused a storm of controversy throughout the country and, as time passed, it began to be realised that this simple—if, as the majority of people thought, misguided—action was to have repercussions far beyond what were at first imagined.

All through April and May the emphasis remained on building. On April 23rd it was announced that work on the foundation of the cathedral was to be started almost at once, while early in May another big step forward was taken towards the completion of the Precinct when work was started on the two link blocks.

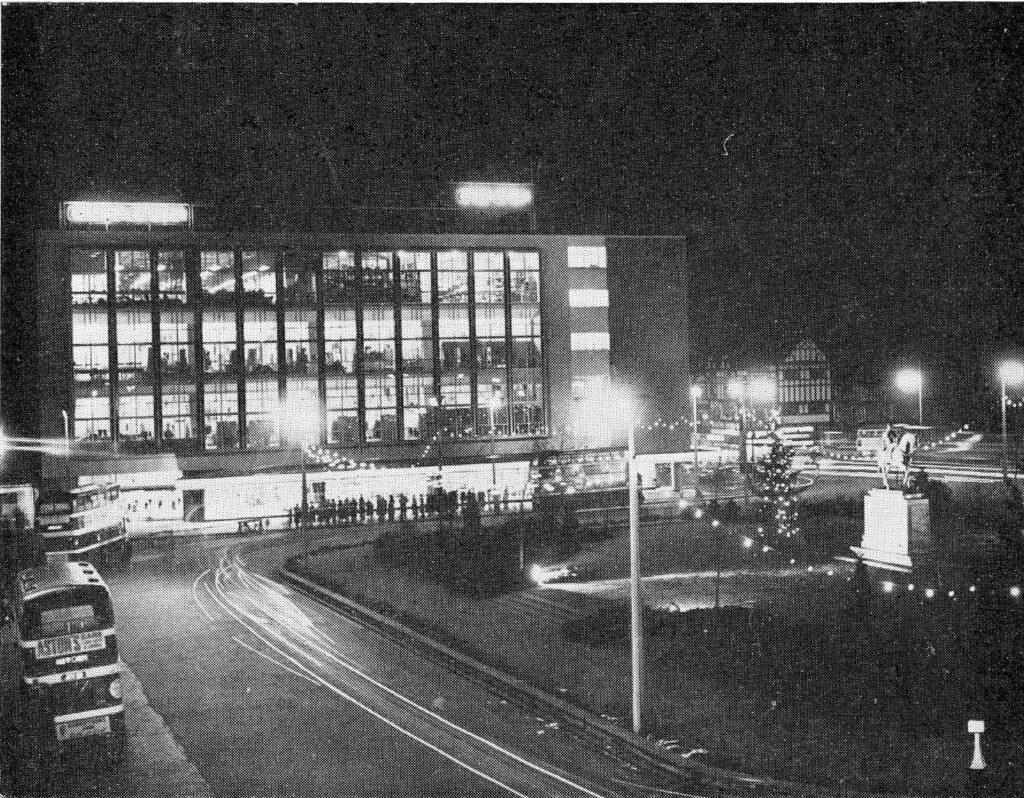

Up until this time, the name of the new hotel which was being built in Broadgate had been in doubt but now it was announced that out of the 1,200 suggested names that had been received the owners had chosen “Leofric”.

But while this hive of commerce was rapidly growing the cultural side of the city was not being neglected for on May 20th Sir Alfred Herbert laid the foundation stone of Coventry’s new art gallery and museum.

Ten days later the Civil Defence controversy flared up anew. On Sunday, May 30th a mobile Home Office Civil Defence Unit was due for a series of exercises in Coventry which had supposedly been the target of an H-bomb.

Instead of a Civil Defence exercise there was nothing but a completely ludicrous fiasco, for Labour members of the City Council hired a loudspeaker van and engaged in a verbal warfare with the Civil Defence loudspeaker van.

Did Coventry approve of the actions of these Council members?

Judging by the letters in the local press it did not. “Shameful Exhibition”, “Crazy and Contemptible Caperings”, “Disgusting Exhibition” were just a few of the comments and there is no doubt that by such—to put it at its best—discourteous behaviour, the Council alienated the feelings of many of those who, up till that incident, had sided with its views.

The matter was even referred to in the House of Commons and the Home Secretary met a delegation from the Council on June 28th.

Early in the following month there occurred a real red-letter day, for on July 3rd meat-rationing ended. After 14 years all food was now free from any kind of rationing.

Again it was Carnival Day and on July 10th one of the most lavish carnival processions—as distinct from Godiva Pageants- wended its £1,500, two-mile-long way out of the Memorial Park. Thousands of spectators lined the streets and more than 30,000 people thronged the Park at night with the result that the Carnival Committee had the satisfaction of announcing a profit of £1,000.

Two days later, the City Council, despite the disapproval that had been voiced on all sides, officially disbanded the Civil Defence Committee. The Civil Defence personnel however decided to carry on until the position was clarified as it was obvious that such a grave step would not go unchallenged.

It did not.

On July 24th the Home Office announced that as a consequence of this action Coventry would lose the 75% Home Office grant and would be called on to pay the whole cost of the Civil Defence Service, a matter of £20,000 annually.

To run the service, the Home Office appointed three commissioners, Air Vice-Marshal Sir Geoffrey Bromet, Major General John Dalison and Miss Mary Gray.

The Council thought these decisions “scandalous” and decided to fight them, but how was not quite clear.

On August 20th it was announced that a new parish was to be created in Coventry from parts of Styvechale and St. Anne’s parishes.

In this new parish, which would serve the Cheylesmore estate, would be built a new church called Christ Church, to replace that which had already been twice demolished

In the following month the Markets and Baths Committee approved a scheme for new central swimming baths which were to be the finest and most modern in the country.

Although everyone agreed that new baths were urgently needed in Coventry the scheme was nevertheless received with mixed feelings —particularly by the ratepayers—when it was learned that the cost of this sumptuous building was to be £750,000.

On October 1st the magnificent new Owen Owen store, which had been designed by a Coventry architect, Rolf Hellberg, and which had cost £940,000 was opened by the Lord Mayor, Alderman J. Fennell, while on the following day the foundation stone of the new Christ Church was laid by the Reverend T. G. Mohan, Secretary of the Church Pastoral Aid Society.

In the meantime a dockers’ strike had once again broken out which soon swelled to alarming proportions for by the middle of October 43,000 men were out.

Towards the end of the month the situation became so serious that exports, particularly of cars, became vitally affected with the result that the Standard Motor Company announced that it would have to close on Friday and Saturday, October 29th and 30th to check production.

Fortunately the strike ended on November 1st just in time to save the livelihood of thousands of workers.

The month closed on two very diverse notes.

On the 29th the whole country was saddened by the death of Sir George Robey, Britain’s “Prime Minister of Mirth”, at the age of 85 years, while on the following day the country united in greeting Sir Winston Churchill on his 80th birthday.

Came December and with it thoughts of Christmas.

The local paper reported that so great were the crowds of early shoppers that extra police were needed to control them.

On December 20th the Cathedral Reconstruction Committee approved the design, by Graham Sutherland, for the huge tapestry 40 feet wide and 80 feet high which was to hang behind the High Altar. This tapestry, depicting “Christ in Majesty” would cost £20,000, take between three and four years to make and weigh 15 cwts.

By the 24th all shops reported record sales while the G.P.O. also broke all records and yet, oddly enough, the Christmas proved to be one of the quietest ever. Perhaps the weather was partly responsible, for it was one of the mildest for many years and temperatures in the 50’s allowed much of the time to be spent out of doors.

Nevertheless the year ended on a gloomy note for on the 30th 12,000 workers at the Standard Motor Company went on strike, while hanging over the entire country was the threat of a railway strike for more pay, and this despite the fact that the British Railways had made a loss of £20,000,000 during the year.